Holocaust Memorial Day

This week, Wednesday 27 January, was Holocaust Memorial Day: an act of national remembrance first commemorated in 2001.

When I was at school in the 1980s I do not recall that the Holocaust or indeed the Second World War was referred to much in lessons. I imagine it was felt that it was still so close in people’s minds that it did not merit that much attention.

In fact, it seemed as though superannuated Nazis were bigger news and incongruous as it may seem one could often view elderly leaders of the Third Reich on comfortable sofas in television studios justifying what they had done or not done. Indeed, one of them, Albert Speer, Hitler’s closest friend, actually died in London having been taken out to a very expensive restaurant by a professor of history at Oxford University as he was making a television show for the BBC.

However, when I began my teaching career in the early 1990s attitudes suddenly began to change and there was a real desire to learn about the Holocaust in schools.

The focus, as it should have long before, turned to the victims not the perpetrators.

I think a lot of this has to do with 'Schindler’s List' - it’s a powerful, although I find very difficult to watch film, about the rescue of 1000 Jews by the German businessman Oscar Schindler.

Uplifting, harrowing and unforgettable it provides an extraordinary insight into the personal decisions which people took in order to allow the Holocaust to occur and how at least one man, Schindler, refused to follow the crowd because he knew what they were doing was wicked and wrong.

But I also think that it has a great deal to do with the fact that Holocaust survivors who had come to live in the UK were coming to the end of their careers and, as they faced retirement, had the time to reflect on things which, perhaps, they had not had the leisure to or not wanted to when they were busy in their careers and bringing up their families.

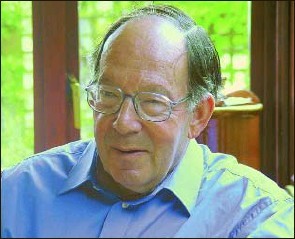

This is the context within with I came to know Paul Oppenheimer. The father of one of my pupils, knew Paul from work and suggested that I might like to have him talk with the boys. After all he only lived just down the road in Solihull. As I had just taken over as Head of History from Alun Vaughan this seemed like a very good idea to me and so I eagerly made contact with him.

This is the context within with I came to know Paul Oppenheimer. The father of one of my pupils, knew Paul from work and suggested that I might like to have him talk with the boys. After all he only lived just down the road in Solihull. As I had just taken over as Head of History from Alun Vaughan this seemed like a very good idea to me and so I eagerly made contact with him.

Paul readily agreed to my request to talk with the boys and I still vividly recall his dry response when I urged the boys to listen very careful as Paul was part of the history they studied.

“Thank you for the obituary, Mr Jefferies”.

The presentation he then gave was wonderful.

What especially struck me was the way in which he relayed what had happened to him and his family with such little drama and in such a matter of fact way that it made it even more powerful and immediate.

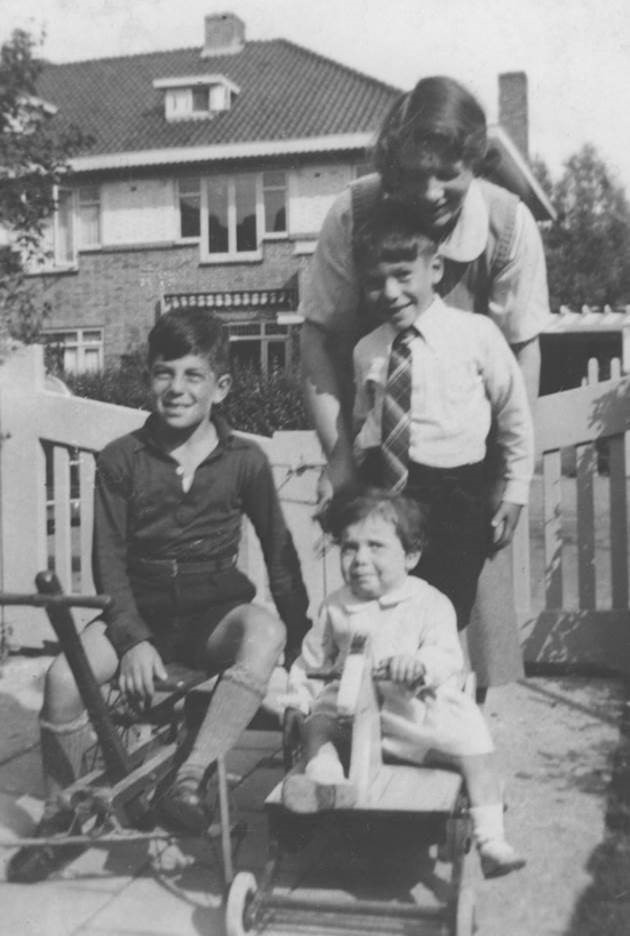

In brief Paul and his brother, Rudi had an idyllic childhood – doting parents and grandparents and a lovely home in Berlin.

In brief Paul and his brother, Rudi had an idyllic childhood – doting parents and grandparents and a lovely home in Berlin.

However, Paul’s parents, Friederike and Johann, were more than most aware of the threat that the Nazis posed to them as Jews. They therefore decided to move the family to England to live with relatives.

This happy ending was though not to last. For some reason Mr Oppenheimer could not join them in England and so moved the family again – this time to the Netherlands, but not before Paul and Rudi’s sister, Eve, was born in London making her, of course, British.

The Netherlands had been neutral in the First World War and so Mr Oppenheimer hoped that they would be safe from the Nazis. However, in 1940 the Germans invaded and once again the Oppenheimers fell into the hands of the Nazis.

From then on their story became darker and darker as they were forced from their home into the Jewish ghetto in Amsterdam, were forced to wear the Yellow Star identifying them as Jews, sent to Westerbork Transit Camp and eventually the dreadful concentration camp Bergen Belsen.

Here the family endured hunger, typhus and SS barbarism but they were not murdered because Eve had a British passport and just maybe the Nazis might be able to use them as hostages as the war ended.

Eventually though their parents died within weeks of each other and just days before the camp was liberated by the British. But just as rescue seemed imminent, Paul, Rudi and Eve, together with hundreds of other exchange Jews, were put on an SS train always keeping one step ahead of the Allies. The train was strafed by aircraft, slowly threaded its way through a bombed-out Berlin until at last the SS ran away and at Tröbitz in East Germany they were finally liberated by the Soviet army.

The children then came to live in England where they swiftly identified as British.

Rudi became an early computer genius, Paul an engineer for which he received the MBE and Eve worked first in a children’s home and then as a glove-maker.

In subsequent years, Paul’s talks became a regular fixture of school life and I learned more and more about him.

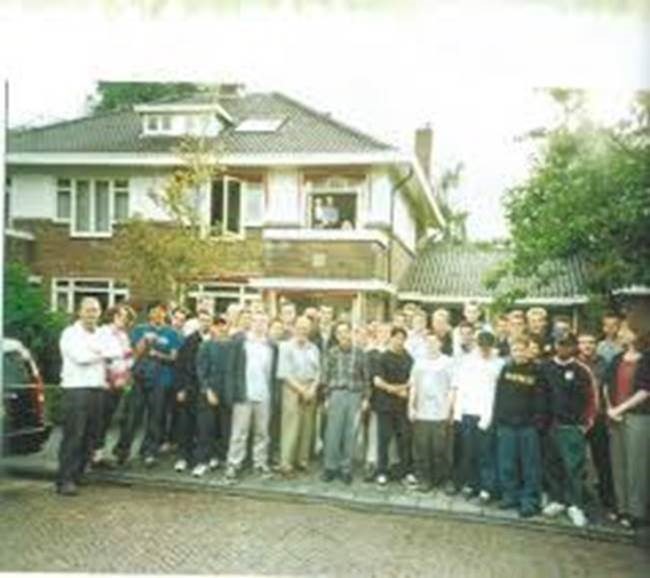

Eventually we decided that we would take a school trip back to all the sites associated with his life. We were joined by Corinne, his wife, Rudi and a very young and enthusiastic member of the History Department, Mr Gibbs.

During eight days we covered almost 1,500 miles. It was an incredible experience and, after thirty years teaching, no other memory is anywhere close.

Some were profound:

Discovering the home in Heemstede from which they were evicted in 1942 and Paul and Rudi being invited in by the family who had known Jews lived there but had thought they had all been killed in the war.

Discovering the home in Heemstede from which they were evicted in 1942 and Paul and Rudi being invited in by the family who had known Jews lived there but had thought they had all been killed in the war.

The boys hushed reverence at Bergen Belsen.

Lighting a candle at Trobitz for one of the boys’ great grandmothers who had been on the same train as the Oppenheimer children but died just before liberation.

But some memories were even funny:

Paul and Rudi having to pay to visit Westerbork transit camp - “It was all free in 1943” grumbled Rudi.

Taking the tram into Weimar in search of food after a dreadful meal at the youth hostel – I think that chef trained at Belsen (again Rudi).

And an officious guide at Belsen arguing with Paul and Rudi about the exact location of their barracks. “Look – that’s not the sort of thing you forget” (Paul).

After the trip Paul continued to talk at the school as often as he could. He even fulfilled a commitment to speak to the boys just weeks before he died in March 2007. I think that he knew that he was dying and exhausted by the over 1000 talks he had given to young people all over the country told me that he had been seriously thinking about “taking it easy” and giving up on his diary commitments. But, as he was toying with this idea, he received a hateful letter in the post telling him that the Holocaust had never happened and that people like him should stop spreading their toxic lies.

That was it, Paul realized. He had to keep on talking to the very end which came just a few days after his final talk at Warwick.

On Holocaust Day in 2007, Paul had told a crowd in Birmingham, “If 60 per cent of people under 35 have never heard of Auschwitz, then ignorance is our challenge. It is our duty to teach them in order to eliminate prejudice. Evil triumphs when good men do nothing and he who does not learn from history is doomed to repeat it.”

I think that could stand as his epitaph.

In the years which followed Rudi took up what Paul had started and generations more of Warwick School boys had the opportunity to hear first-hand about the Holocaust.

In the years which followed Rudi took up what Paul had started and generations more of Warwick School boys had the opportunity to hear first-hand about the Holocaust.

His honesty was often searing.

For example, Rudi told us how he had cleverly secured the job of being in charge of dishing out the soup ration so that he could keep any vegetables at the bottom for him and his brother and father. “I am not proud of this but I was hungry and I wanted to survive”.

But Rudi also loved paradox and took grim pleasure in recounting how as displaced people in 1945, Rudi and his brother were put in a detention camp with SS by overworked and unimaginative British officials. It took a lot of arguing and even more gesticulating to get them out!

Rudi died in 2019 having carried on speaking for many years in spite of progressive cancer.

In all the years I knew Paul and Rudi I never saw them as angry or bitter people and I only ever once saw Rudi argumentative and animated. This is when I took them to Beth Shalom which is an education centre established to encourage an understanding of the Nazi persecution of the Jews as well as to enhance reconciliation and understanding.

They were taking part in a Holocaust survivors’ reunion and wanted me to drive them up there as it was some way away in Derbyshire.

After most of the guests had left a small number of elderly survivors gathered over tea and cake to discuss whether Beth Shalom should commemorate the Jewish Holocaust or other genocides as well. It became quite heated quite quickly. Most thought that the Jewish experience of suffering would be somehow diluted if other genocides were commemorated there as well.

Rudi though was adamant that Beth Shalom had to stand for the suffering of all people who are killed, tortured and victimized as a result of their race. To somehow suggest that the Jewish experience of suffering was unique would be to minimise the sufferings of, he said, the 800,000 Tutsis who had been killed in the Rwandan genocide (1994).

Rudi put it this way,

As a society, we haven't learnt a thing from what happened to people like us.

"That is why I want to keep talking about it. I tell young people that it is up to them to make a better job of running their countries than the previous generations did, and I really hope they do."

In his last years the Syrian migrant crisis especially troubled Rudi and he often regretted that young people in particular were having lives ruined as so many governments and publics looked the other way, complacently equating refugees with terrorists and criminals: throwing up barriers rather than seeking solutions.

I learned so much from these two men but three things in particular stand out for me.

From Paul, that racism and hatred do not go away and that ignoring simply encourages it. That we all have a duty to call it out especially when it happens in the discreet toxicity of social media.

From Rudi, that there is no hierarchy of suffering and that persecution and discrimination in any form must always be confronted. That no group or race can claim a monopoly of victimhood and that what we do as individuals to confront intolerance, whoever it is to, is what defines us as men of good or bad character.

And from both of them, too, I learned that, as immigrants, they always wanted their adopted country to live up to the welcoming idealism which had made them so welcome in 1945.

And what of Eve?

She was the youngest of the children and a girl. The two boys could rely on each other when really bad things happened to them, but she was too young to cope with the feral existence of a child in a concentration camp and the loss of both her parents in such quick succession.

She was the youngest of the children and a girl. The two boys could rely on each other when really bad things happened to them, but she was too young to cope with the feral existence of a child in a concentration camp and the loss of both her parents in such quick succession.

Like them she did survive and she did come to live in England. But she never married, avoided close relationships and could not bring herself to talk about what had happened to her. She died in 2017. Another victim of the Holocaust.

Mr Jefferies, Senior Tutor, Warwick School