Understanding the Actions of Others

How do you react to behaviour that has a negative impact on you? Anger, judgement, and blame? How productive is this reaction? What if the slights you’ve experienced or the harm they have done was not inflicted intentionally? What if the perpetrator thought that they were doing the right thing – for them or even possibly for you?

Socrates said:

'Nobody does wrong willingly'

The Catholic Theologian and Philosopher St Thomas Aquinas had a similar idea. Human nature is essentially good. Humans have a natural inclination to do what is good and avoid what is evil.

'No evil can be desirable, either by natural appetite or by conscious will. It is sought indirectly, namely because it is the consequence of some good.'

According to Aquinas humans would never knowingly pursue evil. They may though pursue an apparent good, something that they wrongly believe to be good. This is an error of reason rather than intention; they are not malevolent but have a flawed understanding of that which is good.

Humans have a natural tendency to judgement of others. This tendency is based on the belief that there is one correct way of seeing the world and therefore one correct way to behave. This position is known as universalism.

For decades universalism, the idea that everyone has the same basic thought processes and humans apprehend the world in fundamentally similar ways was a central tenet of psychology.

‘Māori herders, !Kung hunter-gatherers and, dotcom entrepreneurs all rely on the same tools for perception, memory and causal analysis…etc.’ Richard E. Nisbett

However, the concept of psychological universalism is undermined by the phenomenon of multistable perception, where an image can be perceived by the viewer in more than one way. You may be familiar with one or more of the famous ambiguous images created to induce this experience.

Rubin’s Vase - What do you see, a vase or two opposing faces?

A young lady or an old woman?

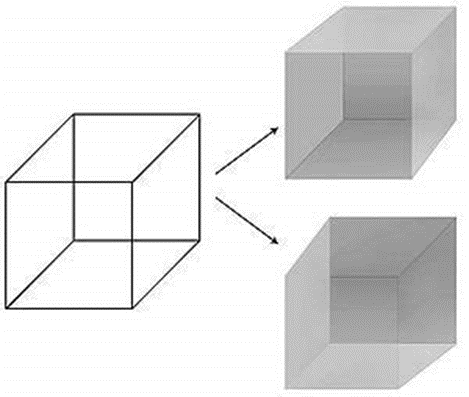

The Necker Cube - a simple two-dimensional wireframe drawing with no visual cues as to its orientation that can be interpreted to have either the lower-left or the upper-right square as its front.

Do you see a rabbit or a duck?

In each case there are two possible interpretations, each of which is consistent with sensory information but only one of which can be maintained at a given moment. Viewers will initially ‘see’ one of the possible interpretations, in most cases they can with time, and possibly explanation access the alternative. In all four ambiguous images we all receive the same sensory information, but our brains process it differently and consequently our experience of the identical image can differ.

In his 2021 book Rebel Ideas; The Power of Thinking Differently the author of Bounce, Matthew Syed refers to a study by two social psychologists, Richard E Nisbett and Takahiko Masuda which has even greater implications for our belief in psychological universalism.

Nisbet and Masuda took two groups – one from Japan and the other from the United States – and showed the same video clips of underwater scenes. They then asked them to describe what they had seen. The Americans talked about the fish, the objects. The Japanese on the other hand tended to talk about the setting, the river in which the fish were swimming. In the next stage of the study the subjects were shown new underwater scenes, with some objects they had seen before and some they had not. The Japanese struggled to identify the original objects. The Americans on the other hand failed to notice the change in setting. The experiment showed that even in our most direct interactions with the world there are systematic differences shaped by culture. The Americans and the Japanese operate with different ‘frames of reference’ or perspectives. The Americans had a more individualistic frame of reference, and Japanese culture is more interdependent and therefore their point of view was shaped by context. Culture impacts the way that we perceive the world.

Ambiguous images and multistable perception, and the work of Nisbet and Masuda indicate that humans do not all have the same basic thought processes. The same stimuli can be experienced and interpreted in different ways based on our individual perspective. In philosophy this is known as perspectivism, the epistemological principle that our understanding of something is always bound to our frame of reference or point of view. In essence we can only experience the world through our own eyes, a lense that is shaped by a range of factors including our physical circumstances, and culture. Nisbet and Masuda’s American’s viewed the video clips through an ‘American’ object centered and individualistic filter and the Japanese subjects in their experiment saw the underwater scenes from a Japanese point of view. The same stimuli, different experiences neither wrong just different.

What are the implications of perspectivism for morality?

(Normative) Ethical relativism is one possible conclusion. Ethical relativism is the view that it is wrong to pass judgement on other cultures and individuals who have substantially different ethical values that are based on a different frame of reference or perspective. For example, it would be wrong for the monogamous Anglican to judge the polygamous Mormon.

However, rejecting psychological universalism, accepting that we think differently, have different frames of reference, and that it is impossible for us to ‘see’ the world through eyes other than our own does not mean that we must accept abhorrent behaviour. Friedrich Nietzsche was a perspectivist, but he was not a moral relativist who believed that all frames of reference were equal. For Nietzsche we cannot escape from our own point of view, but we can understand that our perspective is merely that rather than objectively true, and those perspectives which appreciate their subjective nature and are of the greatest ‘value for life’ are superior to others. Similarly substantial relativists like David Wong argue that whilst there is no single true morality some moralities are wrong. According to Wong morality exists to regulate conflicts of interest between individuals where those interests cannot be simultaneously satisfied. Very different moralities constructed by societies with different perspectives can adequately perform this function. Those that do not are wrong. Thus, our tolerance of alternative points of view does not require us to accept colonialism or national socialism.

The responsibility to make the world a better place and the humility to listen to and respect others are two of the values that form the Warwick Way. If other people experience the world differently as multistable perception and Nisbet and Masuda imply, and Socrates is right that ‘nobody does wrong willingly’ then these values require that we understand the actions of others, whether we agree with them or not, as attempts to do the right thing informed by a different perspective. How radically would this lens change our reactions. The appreciation that our point of view is just one of many is likely to lead to a greater degree of understanding, empathy and tolerance and mean that our reaction to actions and behaviour that impact us negatively is more productive than the blame and anger it is all too human to feel.

The Stoic philosopher and Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius summed this up in his Meditations.

‘Whenever someone has done wrong by you, immediately consider what notion of good or evil they had in doing it. For when you see that, you’ll feel compassion, instead of astonishment or rage. For you may yourself have the same notions of good and evil, or similar ones, in which case you’ll make an allowance for what they’ve done. But if you no longer hold the same notions, you’ll be more gracious for their error.’